How to Write Faster Code Than 90% of Programmers

Most programmers write code for an abstract computer. The thing is- code runs on a real computer that works in a specific way. Even if your game is going to run on a wide range of devices, knowing some of the common features can speed up your code 10x or more. Today’s article shows you how!

Broadly, all modern computers have the same configuration. They have a CPU, a GPU, and RAM. The CPU also has two or three levels of cache: L1, L2, and L3. Those caches are used to speed up RAM access because it is so slow. Exact numbers will vary by device, but according to this site here are the rough speeds:

- L1 cache access: 1 nanosecond

- L2 cache access: 4 nanoseconds

- RAM access: 100 nanoseconds

This means that there’s a 25-100x advantage to using the memory that’s in the CPU’s cache compared to memory that’s in RAM.

Unfortunately, most programmers never think about this. For example, consider languages like C# where almost everything is a class allocated in RAM by the VM. Your class reference is essentially a pointer to a random location in RAM. An array of class instances therefore looks like this in RAM:

| 49887 | 32704 | 21426 | 53253 | 11753 | 71510 | 9790 | 40224 | 88383 | … |

Each of these entries is a pointer: a memory address. When you loop over these class instances and access them you’re essentially visiting random locations in memory. What are the odds that this random memory location is in one of the CPU’s caches? Virtually zero.

You see variations of this code all the time. Almost everything is some kind of class and almost every container—List, Dictionary—is looping over instances of those class. It’s rare in C# programs to see any code that acknowledges the existence of CPU cache.

So what if you wanted to take advantage of the CPU cache? I figure this would put your code in the top 10% in terms of performance, purely based on my experience reading a variety of code throughout my programming days. Fortunately C# is friendlier in this respect than languages like Java or AS3. It often comes down to using struct instead of class.

Say you have an array of structs instead of an array of classes. A struct is just its contents. There’s no pointer to the struct like there is with a class. So the array of structs is just the array of their contents. When you access the first one, the CPU loads a bunch of memory into its caches starting with that struct. That means when you access the next struct in the array it’s already in the cache.

Let’s see how this looks in practice. The following script has a ProjectileStruct and a ProjectileClass each with a Vector3 Position and Vector3 Velocity. It makes two arrays of them, shuffles them, and loops over them calling UpdateProjectile for each one. That function just moves the projectile’s position according to a linear velocity: projectile.Position += projectile.Velocity * time;.

Note that this is a similar test to this article but with several important differences.

using System; using UnityEngine; class TestScript : MonoBehaviour { struct ProjectileStruct { public Vector3 Position; public Vector3 Velocity; } class ProjectileClass { public Vector3 Position; public Vector3 Velocity; } void Start() { const int count = 10000000; ProjectileStruct[] projectileStructs = new ProjectileStruct[count]; ProjectileClass[] projectileClasses = new ProjectileClass[count]; for (int i = 0; i < count; ++i) { projectileClasses[i] = new ProjectileClass(); } Shuffle(projectileStructs); Shuffle(projectileClasses); System.Diagnostics.Stopwatch sw = System.Diagnostics.Stopwatch.StartNew(); for (int i = 0; i < count; ++i) { UpdateProjectile(ref projectileStructs[i], 0.5f); } long structTime = sw.ElapsedMilliseconds; sw.Reset(); sw.Start(); for (int i = 0; i < count; ++i) { UpdateProjectile(projectileClasses[i], 0.5f); } long classTime = sw.ElapsedMilliseconds; string report = string.Format( "Type,Time\n" + "Struct,{0}\n" + "Class,{1}\n", structTime, classTime ); Debug.Log(report); } void UpdateProjectile(ref ProjectileStruct projectile, float time) { projectile.Position += projectile.Velocity * time; } void UpdateProjectile(ProjectileClass projectile, float time) { projectile.Position += projectile.Velocity * time; } public static void Shuffle<T>(T[] list) { System.Random random = new System.Random(); for (int n = list.Length; n > 1; ) { n--; int k = random.Next(n + 1); T value = list[k]; list[k] = list[n]; list[n] = value; } } }

If you want to try out the test yourself, simply paste the above code into a TestScript.cs file in your Unity project’s Assets directory and attach it to the main camera game object in a new, empty project. Then build in non-development mode, ideally with IL2CPP. I ran it that way on this machine:

- LG Nexus 5X

- Android 7.1.2

- Unity 5.6.0f3, IL2CPP

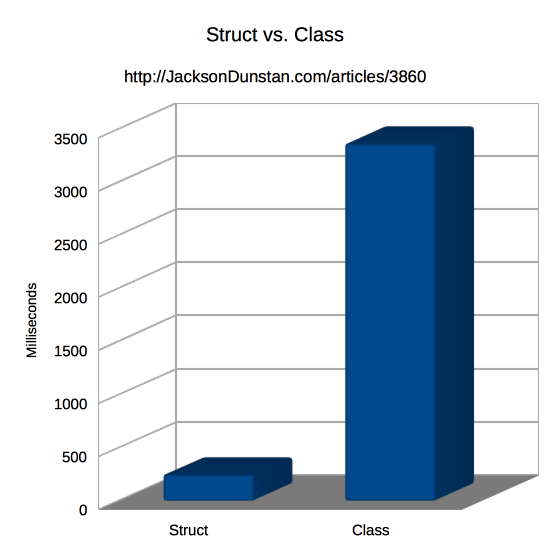

And here are the results I got:

| Type | Time |

|---|---|

| Struct | 250 |

| Class | 3365 |

As predicted, roughly, by the CPU cache and RAM access times, we have a 13.46x speedup by using cache-friendly structs instead of classes. That’s a huge win! Who wouldn’t like their code to run an order of magnitude faster? By organizing your data in cache-friendly ways, you can realize huge performance increases over almost every C# programmer who sticks to the default, class-oriented programming style.

It’s worth noting that just using the CPU cache still leaves a ton of performance on the table. For example, you’ll need to use multiple threads to take advantage of all the CPU’s cores. You’ll need to max out the GPU, too. Games often do this with graphics rendering, but increasingly there is more general-purpose work to be done there with the likes of compute shaders. Those are topics for another day.

#1 by Valerie on May 8th, 2017 ·

Can’t wait to implement this in my code and see the effects on performance and speed. Of course based on the title, my small brain thought I was gonna write code in 90% less time LOL.

Definitely looking forward to learning how to max out the GPU.

Thanks JD!

#2 by Adam on May 8th, 2017 ·

Really glad I stumbled across this! Great article.

Are there drawbacks to overusing structs?

#3 by jackson on May 8th, 2017 ·

I’m glad you enjoyed it. :)

Yes, there are some drawbacks to using structs in C#. They don’t support inheritance, but you can implement interfaces. You can’t define a default constructor, so you need to set them up so that the default value for all the fields is what you want and/or provide an

Initializetype of function.This page from Microsoft has a good rundown on the differences.

#4 by Frank on May 8th, 2017 ·

According to Microsoft structs should be immutable since treating them otherwise invites performance hits such as unintended copies due to passing by value.

#5 by jackson on May 8th, 2017 ·

That’s one way to use them, but clearly not followed in most cases. For example,

Vector3in Unity is mutable.Structs are just a language feature and you’re free to use them as you wish. As long as you understand how they work (e.g. pass by value unless you use

reforout) then I don’t see any reason to adhere to such an arbitrary rule.#6 by Asik on May 11th, 2017 ·

The big no-no is an instance method on the struct mutating it. If that instance lives in a readonly field, your method will do **nothing** (it will be invoked on a temporary copy) and that’s super confusing.

Structs get copied around when passed by value so if you’re mutating it you have to be aware of which copy it is that you’re mutating (and if it’s passed by reference, what is it a reference of).

Immutable structs save you from having to think about these issues and the associated bugs from not thinking correctly about these issues. They come with a cost though (overwriting the whole struct is more expensive than overwriting just the field you want to change), so if you’re optimizing for performance, choose carefully.

#7 by jackson on May 11th, 2017 ·

This is an excellent tip. You should definitely beware of the interaction between

readonlystructs and methods that modify them.#8 by Robinerd on May 8th, 2017 ·

Interesting! Agree that we should all consider the caching more often. Though I find that most of the lists/arrays we loop over are other scripts inheriting from mono behaviour, so mostly this can’t be used. In a few places we use inner structs for storing data used by some performance heavy algorithms, typically handling hundreds, or thousands of instances. Those few places would probably hit the performance noticeably if using class instead of struct.

#9 by kaiyum on May 8th, 2017 ·

Great article! One question: Struct normally does “pass by value”, isn’t it? So if I have a pretty big struct within a loop(worse loop inside a loop), then would it not eat up the stack quickly?

Between, is there any other way to utilize cache in C# apart from struct treatment?

#10 by jackson on May 8th, 2017 ·

Yes, structs are “value types” as opposed to classes which are “reference types”. So if you assign a struct variable to another struct variable or pass a struct as a parameter to a function then a copy will be made, just like it would with

intandfloat. You can turn this off in the case of functions by adding thereforoutkeyword like I did in the article. When you do that you’ll get “reference semantics” even though the struct is a “value type”. Unfortunately there’s no such thing as areflocal variable, so you’ll need to use pointers for that purpose.Structs are just one way to make better use of CPU caches in C#. An array of structs works because the array elements themselves are arranged sequentially in memory. Using an array (or

List) in the first place is a good example of a cache-friendly data structure. Compare to aLinkedListwhere each node is an individual class instance located (essentially) randomly in memory.#11 by James Casey on May 9th, 2017 ·

Interesting stuff. I am an amateur, can you help me complete the picture? In the context of Unity, how would you go about drawing those projectiles to the screen? To my basic understanding, you would need a GameObject (i.e. a class) anyway?

#12 by forrest gump on May 10th, 2017 ·

have you looked at all the Unity tutorials ?

go here and scroll down

https://unity3d.com/learn/tutorials/

#13 by jackson on May 10th, 2017 ·

You don’t really have any choice but to use the Unity API since you’re writing a Unity game, so in the end you’ll probably be dealing with some class types like

GameObject. However, you’re free to organize your game data however you like. In the article’s example, you’d be updating your projectile positions really fast by taking advantage of the CPU cache but then telling Unity about those updated positions viaTransform.localPositionset calls.#14 by Irne Barnard on May 9th, 2017 ·

This is definitely a very good idea … for certain scenarios. One of the very reasons C# (and most of DotNet) can give better performance than some similar environment like Java (and the other JVM languages – it doesn’t have such by-value types). Structs “can” give awesome cache optimisations. However, there are places where they tend to make less sense and could even cause degradation in performance.

E.g. due to the pass-by-value nature of a struct, every time you send/receive a argument/parameter into another method a copy of the values inside the struct is passed. Doing such copy does take time, not to mention the copy actually resides in a new spot in RAM as well. By preference a struct should contain only small items, a few ints/floats should be fine. It should by preference not contain another by-reference value (such as strings and arrays). And it should definitely not contain huge quantities of these.

The main reason MS suggests structs should be immutable is because of an optimisation technique used in the CLR, where function calls are inlined. If the JIT compiler notices that the parameters are only used as values, it could rather just take the code inside the function and insert it into the spot where the function was called. However, if the struct gets changed this becomes problematic and such inlining is avoided, causing the by-value copy scenario above, and thus also loosing cache optimisation.

As you’ve mentioned, if prefixing a ref/out parameter decorator, this concern may be avoided. Though such isn’t always what the programmer wanted – thus this “speedup” is only for select circumstances and shouldn’t be used as a common one-type-fits-all idea.

#15 by jackson on May 9th, 2017 ·

Very well said! These are excellent points about structs as a value type. Understanding that—just like understanding classes as reference types—is key to effective use of them.

I wonder about how applicable the advice to use immutable structs is when running with IL2CPP as the scripting environment. A C++ compiler will bring a completely different set of optimizations along with it, so that advice may or may not still hold. For running C# on Microsoft’s .NET VM it’s much more likely to apply, but even there it would be a good idea to profile to be sure.

#16 by DS on May 9th, 2017 ·

This is a terrible idea.

While structs are useful and have their place, their overuse will lead to really, really disgusting code that is hard to use, buggy as hell, unpredictable & probably prone to stack issues.

Overuse of structs will lead to really sucky, really inelegant code that developers will hate using, hate maintaining and hate contributing to.

Don’t believe me? Fork and port one of the larger .NET projects on GitHub to using this structs idea and see how far you get. Entity Framework as it could do with a 90% speed improvement. Pretty sure you’d be tearing your eyeballs out before you converted 30% of it over to structs.

Put your money where mouth is. Let’s see you turn an existing, well-known piece of software into something 90% faster using structs.

#17 by jackson on May 10th, 2017 ·

The point of the code in the article is to illustrate that the CPU cache is an order of magnitude faster than RAM and that we have access to that performance gain even in C#. Looping sequentially over an array of structs is a convenient way to show that. In some areas of your code you might desire higher performance and this is one tool that you can use to get it. Like all tools, they don’t apply universally. Classes certainly make more sense than structs in many scenarios, just as dictionaries make more sense than arrays in many scenarios. So I won’t be porting any large .NET projects to use only structs because that is not what this article is advocating.

#18 by vladest on May 9th, 2017 ·

Its nice to talk about non-abstract machine optimization in sandboxed environment like C#

Taking in account most of today’s “developers” have no any clue what L1/L2 is (hello, js/html/css perfect world)

#19 by Buzz on May 10th, 2017 ·

and if the Structure contains class instances – does that impact performance?

#20 by jackson on May 10th, 2017 ·

Yes, in several ways. From a CPU cache standpoint, accessing those class fields is essentially accessing a random location in memory and will most likely result in a cache “miss”.

#21 by David Gray on May 10th, 2017 ·

It amazes me how many people half-read the article, then write a comment that demonstrates for all to see that the reader missed a key point. For example, nowhere did you suggest abandoning classes for structs. What you did say, and explain quite well, is that they are part of the language for a reason, and that there are times when their properties make them much more efficient.

As with most everything in software design, optimization is almost always about choosing your battles and your algorithms wisely. While I don’t write games, nevertheless, I was inspired to consider when, in the types of programs that I do write, it might be beneficial to trade small classes for structs. That said, I have used structs, sparingly and judiciously, I think, when I felt that the overhead of a class was too much for the case at hand. I hadn’t considered the potential for cache optimization, but I now have food for thought for my next project where that might matter.

#22 by DS on May 10th, 2017 ·

I read the article completely​. The author doesn’t suggest throwing classes out completely, but doesn’t suggest using structs judiciously either. This *is* a key point. In fact, the tone of the article infers that they should be preferred! Examples –

“It often comes down to using struct instead of class.”

And

“… you can realize huge performance increases over the almost every C# programmer who sticks to the default, class-oriented programming style.”

This potentially damaging to new/amateur developers, of which a number have commented here.

Preferring structs over classes would be a nightmare. Readability would suffer. Extensibility would suffer. Performance could actually go backwards from assignment operations (especially if the struct size is nontrivial), boxing/unboxing to reference types. The list goes on!

While it’s possible to optimize code to make better use of memory through structs it can’t be done through their​ blanket use. This is not mentioned in the article and it absolutely should be. The gist of the article is “Speed your code up by 90% by using structs instead of classes” which is patently and utterly wrong. It would be better if the gist of the article was “Speed up some small parts of your code a significant amount by using structs carefully” as this is closer to the truth.

I still agree that structs have their place and they can improve performance IF used wisely. I’d rather start with a class and refactor to a struct if need be than start with a struct and paint myself into a corner.

#23 by Richard on May 10th, 2017 ·

This is a very interesting idea, in that it points out a huge weakness in how C# class constructs constantly go out and hit the RAM. It is my expectation the programming language framework and compiler automatically optimizes the code to use the CPU cache whenever it is practical, and that should be every programmer’s point of view. The idea of using structs instead of classes cleverly illustrates how you CAN make code run faster by forcing it to use the CPU cache. But I have to agree with DS – that should not be adopted as a standard programming practice. It should only be used if the programmer is faced with a computationally intensive problem to solve. This article should have been written with that point of view.

#24 by jackson on May 10th, 2017 ·

It’s important to test your assumptions about performance, such as by profiling. Performance will vary wildly by many factors. For example, IL2PP performs quite differently than Mono and neither performs the same as .NET. In the case of CPU caching, none of these environments guarantee that instantiating a class will place it sequentially after the previously-instantiated class. That means you can’t guarantee the sequential memory access critical to effective use of the CPU’s caches. An array of structs, on the other hand, is guaranteed to have sequential layout in RAM in all environments.

#25 by Hamza Ahmed Zia on May 10th, 2017 ·

Well written judicious article.

The point made by the author is choosing the right construct for a particular scenario.

I will definitely “think” a little more in favour of structs over classes for DTO’s.

Reminds me of using StringBuilder over plain String when manipulating text on the DotNet Framework.

Thanks Jackson

#26 by John Morrison on May 10th, 2017 ·

This reminds me of the assertion that C# and Java can be written to compete with C++ on performance. Yes, but only if you avoid any kind of object orientated programming. That is of course very uncomfortable. Much more uncomfortable than writing in C++.

#27 by James Curran on May 10th, 2017 ·

>> Yes, but only if you avoid any kind of object orientated programming.

Sorta — To ensure C++ is faster, you have to avoid many OO techniques (stick to native types that can be easily inlined)

Raymond Chen (MS Systems programmer) wrote a simple C++ program. The C# PM took it, and wrote a quick port in C#. The C# version was faster. Chen then took his program and went through 5 rounds of re-writes of it (documented in a series on his blog) until he finally got the C++ version faster than the C# version. This involved rewriting hunks of the C++ standard library.

The bottom line is, for the most part, the framework/OS/compiler knows how to manage memory better than you do.

#28 by Kay on May 10th, 2017 ·

“The bottom line is, for the most part, the framework/OS/compiler knows how to manage memory better than you do.”

AMEN.

#29 by jackson on May 10th, 2017 ·

This really depends on how well you know how to manage memory. You, the programmer, have huge advantages that can lead to huge performance increases. I hope the code in the article makes that clear.

#30 by James Curran on May 10th, 2017 ·

Your code is designed to particular highlight the differences. If the arrays were smaller, or if the objects weren’t shuffled, or, if the structs were larger, or (most importantly) if structs weren’t in an array, the results would be far closer.

By putting the struct in an array, as soon as you read the first element, the whole memory block is read in, so the next N elements (depending on struct size) are read into the cache. Hence, by reading them sequentially you are reading things that are already in the cache. But, when you created the class object, they would also be put into sequential memory — hence the need to shuffle them, and the need to shuffle 10 million of them, so there’s little chance that two sequential object are in the same cache block.

If, instead of shuffling the arrays, you instead called UpdateProjectile on the object in a random order (the act you are trying to simulate by shuffling), you’d probably very similar timings.

#31 by jackson on May 10th, 2017 ·

Yes, the code was designed to highlight the difference in performance between CPU cache and RAM and you’ve identified some key elements. I’ll explain a bit more about why certain decisions were made:

A large array was chosen to produce large enough numbers in milliseconds that I could measure it. The performance would be roughly the same unless the array was very short. You could certainly lop off a zero or two and get similar numbers.

The arrays were shuffled because the memory allocator just happened to allocate all the class instances roughly sequentially. That defeated the purpose of the article, which was to show the performance difference between CPU cache and RAM. That sequential allocation is also not guaranteed, so it would be a very dangerous assumption to rely on it. There are a great many cases where you will not get sequential memory allocations for classes, especially as the heap grows more and more fragmented.

I didn’t test multiple object sizes. It would be interesting to see how the results vary when they grow beyond the current 9 floats.

An array is critical to this test. Without it you’re not guaranteed sequential memory layout. For example, a linked list would result in cache misses at every node visited. Since the point of the article was to highlight how you can arrange data to be cache-friendly, I went with an array.

#32 by Asik on May 11th, 2017 ·

The GC heap doesn’t really tend to become fragmented as GC performs compaction every now and then (exception made of LOH and if you’re pinning anything of course). You certainly can’t guarantee sequential allocation, but that’s what you’ll have the vast majority of the time. So by shuffling the arrays here you’re really demonstrating an artificial worst-case rather than typical performance. Of course one might actually shuffle an array of reference types in a real-world application, in which case it’s nice to know this will degrade performance significantly; but reading this article you wouldn’t know it’s reference types + shuffling that killed you rather than just reference types.

Definitely there’s a good take-away point here that memory locality matters. I certainly agree with the conclusion that arrays of structs are super fast and precisely because of locality, but the numbers are a bit misleading without a full explanation of why reference types perform so poorly in this particular case.

#33 by jackson on May 11th, 2017 ·

It’s a good point that in some circumstances you may get sequential allocation for classes, too. GC heap allocation strategies will vary quite a bit from environment to environment though. Unity’s (ancient) Mono, IL2CPP, and .NET behave quite differently. There will also be variation based on the state of the managed heap. Unity’s Mono is notorious for heap fragmentation, so we’re often not getting sequential allocation.

Even with sequential memory allocation, there are many more ways than shuffling to end up with non-sequential class objects. In fact it seems rare that I ever see an array of classes filled up immediately with consecutive allocations.

An array of structs, on the other hand, is guaranteed to be contiguous in memory so there’s no question that you’ll get the best CPU cache performance. The code in this article was designed to demonstrate the difference in CPU performance between CPU cache and RAM and this was the best way to do it, even if in some circumstances you may luck out and get sequential allocation with classes. I certainly didn’t want to imply that you could count on that though.

#34 by Collin on May 10th, 2017 ·

Very good article.

Vectors are used everywhere in game programming; cameras, collision detection, effects, object movement, line of site, path finding, graphics, etc,etc. They are also constantly being created and destroyed; thousands and thousands of them every 1/30th of a second if you are running a 30 fps game engine. Vectors are a perfect example of when to use structs and a class implementation of a vector will absolutely destroy your performance.

Anyway, this article inspired me to revisit a piece of code that iterates over multidimensional result sets and creates thousands, or tens of thousands, of intersections and is slow. Maybe some judicious use of structs will help. Thanks!

#35 by Unni Mana on May 10th, 2017 ·

Very informative article. Btw, which version of C# offers support for ‘Struct’

#36 by jackson on May 10th, 2017 ·

All versions of C# include support for structs.

#37 by Pedro Ramirez on May 10th, 2017 ·

Structs are good, but are not recommended in many situations, I mean they are not a substitute for classes, first of all, they are allocated differently as many have pointed, and the main problem with where they are allocated is that you will run out of memory very quickly if you use them intensively, others have also pointed why Microsoft recommend them to be immutable.

#38 by jackson on May 10th, 2017 ·

Structs are allocated in one of three places.

First, local variable structs are allocated on the “stack” which is limited in size depending on your platform. For example, it may be just 1 MB. Usually you don’t run out of stack space, but you could if you went wild with a bunch of humongous structs or deep recursion.

Second, struct fields of structs are allocated sequentially in the struct. In the article,

Positionis right beforeVelocityin memory.Third, struct fields of classes are allocated along with the class in the “heap”. This is essentially RAM which is typically very large these days. In this case there’s not much difference between structs and classes as classes are always allocated in the heap.

#39 by SteevenPlu on January 27th, 2019 ·

Thanks for your metrics. Numbers are better than words :)

Technically, your test matches the benefit you can met on Data-Oriented Design/ECS Design.

I have an extra-question about “stack or heap” in C#. I am cpp programmer and my C# level is occasional (and restricted for Unity).

But by reading .NET specifications, I have seen these lines

“AVOID defining a struct unless the type has all of the following characteristics: […] – It has an instance size under 16 bytes. […]”

16 bytes seems to me quite shorts O_o

so I made an experiment. I made a “kind of static assertion” to ensure some struct are stack-ready for C# each time I modified the code”.

I use it in my project with [DidReloadScripts]

with the following type definition

The result are:

Quaternion => Ok (16 bytes)

Vector3 => Ok (12 bytes)

PhysicProperties => OK (8 bytes)

KinematicState => Fail (76 bytes)

Body => Fail (84 bytes)

^^your projectile {Position/Velocity} would failed the assertion (2 x vector3 => 24 bytes?)

Do you know if the the 16 bytes constraint is upped on Unity implementation or would your struct be allocated/deallocated on heap (and so the benefit is due to CPU-cache only)?

Thx :)

(PS: Not having a clear control on what is on heap & stack sometimes make me crazy with C# :p)

#40 by jackson on January 28th, 2019 ·

C# actually gives you complete control over whether your data goes on the stack or the heap. You don’t get a lot of control over where it goes on the stack or heap, but you can at least avoid the heap if you want to. In short, managed types (e.g. classes and delegates) and their fields are allocated on the heap and everything else is on the stack.

C# and the underlying runtime such as IL2CPP or .NET don’t decide to allocate on the stack or heap based on the size of an object. There is no “16 bytes constraint,” just an arbitrary guideline from Microsoft. The guideline exists to help programmers avoid a lot of object copying since assignment, parameter passing, and returns of structs are all copied by value just like in C++. You can avoid this using the

ref,out, andinkeywords on parameters, which forces passing by reference just like in C++ withT¶meters.#41 by forrest gump on May 10th, 2017 ·

great article

reminds me of this section from Game Programming Patterns

http://gameprogrammingpatterns.com/data-locality.html

#42 by jackson on May 10th, 2017 ·

Wow, that is a great article. Thank you for linking!

#43 by Terrance Van Gemert on May 10th, 2017 ·

Well well this nothing new as years ago long long before Class or OOP’s came about Struct was used to create a array in memory.. hence the old process of malloc(sizeof(8))It was later moved to the Cashe level for the reasons of speed. NO need to dash out to the memory array.. but really pull in data and hold use then throw away.. It is used for math process of very long Quadratic equations.

But most of all L1 and L2 is the fast zone to memory which allows for very fast but not secure access to memory as any program can access the array.. so do you really want to keep sensitive data in the L1 or L2 Cache.. Think before you stink… If you really want to hold it have Structs inside a Class.. so that data is processed as fast as possible and thrown away.. Remember Malloc based on structure is required in order to know the size of the object.. if not known then huge blocks are taken. which is faster.. defined size of memory allocation or large blocks.

So when one calls Struct the process now uses the Malloc ( Sizeof( the sum of the parts within the structure, which are of defined types) )

It is best to keep a record of the size when one wishes to use pointers within a class only

using New on a structure will fail in code.

But this is going back to the beginning of real programmers who do more effort up front to make program as small as possible and maximize speed while keeping track of security concerns.. It takes along time to code but the payoffs are shown later as there is no holes to exploit.

Think about using a combo of C++ code for your own class objects then use a wrapper like Visual Basics or C# to handle flow and access controls along with create and delete functions.. When you do this make sure you throw away unneeded or no longer required, Malloc or Calloc, structs by doing a free call to release.

Failing to do so will result in memory leaks and yeah memory will be swallowed up.. Fast if it is call over and over again…

Really this is no secret to programmers who study and learn the base languages first then work up to the higher languages. Like VB or C# etc.. Those are top level class control languages. C is going back to the days of peek and poke.. on the shared structure memory for pins on a input like Serial or parallel ports. Those are structures which are fixed and used the same way.. Just knowing where to point and look or set is the question.

#44 by Groo on May 10th, 2017 ·

Interesting article, but I think the difference might not be caused by caching, but rather due to the cost of indirect access for classes and perhaps compiler optimizations for the struct version?

Perhaps I am mistaken and did something wrong, but to test this assumption, I used array indexing though a third (shuffled) array of indices, to remove any cache benefits for the struct variant too:

// create an array of random indices

int[] indices = Enumerable.Range(0, count).ToArray();

Shuffle(indices);

…

for (int i = 0; i < count; ++i)

{

// use random 'indices[i]' to jump all around the 240MB array

UpdateProjectile(ref projectileStructs[indices[i]], 0.5f);

}

// same for classes

I got these results (i7 sandy bridge):

Sequential access (i.e. original article):

– Struct: 200 ms

– Class: 760 ms (3.8x slower)

Random access (the code above):

– Struct: 700 ms

– Class: 2,100 ms (3x slower)

So, it looks like accessing the arrays through the

indicesarray seems to create substantial overhead, but the *relative* difference in performance seems very similar in both cases. If you looked at the latter test alone, what would you conclude about the role of caching between these cases?Since this article got some publicity through the CodeProject mailing list, perhaps it would also be a good idea to state the downsides in using large struct arrays (i.e. in this case, struct array needs a 6x larger contiguous block of RAM on a 32-bit machine, compared to the class version which only stores pointers; it’s easier to get

OutOfMemoryexceptions with large arrays). They also have different semantics (passed by value, i.e. cloned on each pass to a method), so this might be confusing unless they are immutable.But as long as the structs contents are small and arrays don’t have millions of elements, I agree it’s worth trying them and profiling, not just for direct accessing and the mentioned cache locality, but for lower GC burden too.

#45 by jackson on May 10th, 2017 ·

Could you elaborate on what you mean by “indirect access for classes”? As described in the article, class instances are pointers and this is the root cause of the cache misses in the test code. I think if you give me a better idea of what you mean by that I’ll understand your point and your indices example more clearly.

Also, could you describe your testing environment? I see you’re using a Sandy Bridge Core i7, but Unity doesn’t support IL2CPP on standalone builds or in the editor. The Mono2x scripting environment will certainly have very different performance characteristics.

As for memory usage, the struct version actually uses half the memory than the class version. Each element of the struct array contains a struct with two

Vector3structs each containing threefloatfields at four bytes each. That’s 24 bytes per element. The class array contains four or eight bytes per element (usually eight these days) to store a pointer. So yes, the class array itself takes more memory than the struct array but the class version still has to store class instances containing the vectors. On top of that, the class derives fromIl2CppObjectwhich contains two more pointers while the struct doesn’t derive from anything. So the total storage of each element in the class array is 8 (pointer) + 24 (vectors) + 8*2 (base class) = 48 bytes per element.Thanks for the thoughtful comment. :)

#46 by Groo on May 13th, 2017 ·

Hi, I just ran the code outside Unity, as a plain C# application, removed the MonoBehavior reference. Also, I didn’t have Monogame installed on that machine, so I quickly wrote the Vector3 class with + and * operators.

Tl;dr check the gist here: https://gist.github.com/vgrudenic/545c338b99a90a971ca5c53da523f23f

I was aware the results would be slightly different, but I just wanted to check if the difference between struct/class arrays would be lower if access was made through random indices for structs too.

#47 by jackson on May 14th, 2017 ·

It’s hard to say in this case. You’re running on some x86 CPU instead of ARM, desktop .NET or Mono instead of IL2CPP, Windows or Mac instead of Android, your own pure C#

Vector3implementation, and you’ve refactored the test code quite a bit further than was necessary to get it to run outside of Unity. That’s too many changed variables for me tell why you’re getting different test results. Also, I’m still not sure what you mean by “indirect access for classesâ€.#48 by Groo on May 15th, 2017 ·

I am sorry if I was unclear. By “indirect access” I meant just the additional step of dereferencing the array pointer, vs simply reading the value for the struct case. But basically what I meant was, “perhaps the 10x difference is not caused by caching (at least not completely)”. There is overhead in using reference types, unrelated to caching, so I wanted to see exactly how much of the speedup is caused by caching alone.

My point also isn’t that I am getting different test results, I don’t care if I got a factor of 5x, 10x or 100x. My point is that (on x86, at least) the struct array version beats the class array version even if you randomly access the struct array. This is why I refactored your code, to do both a sequential and random test and compare them.

So, my conclusion so far is: When you randomly access both the struct array and the class array, there is still a difference in performance, slightly lower, but of a similar range of magnitude.

Sorry if I refactored the test code further than was necessary, but I thought I express the only important part in the first comment, namely:

int[] indices = Enumerable.Range(0, count).ToArray();

Shuffle(indices);

// and then:

for (int i = 0; i < count; ++i)

{

// random access, no caching

UpdateProjectile(ref projectileStructs[indices[i]], 0.5f);

}

To spare you the trouble, I created a gist you can test yourself: https://gist.github.com/vgrudenic/c0617744748253be20260aacfe22aaf5. Perhaps running this on Unity + IL2CPP + Android will show different CPU caching behavior, but my assumption (solely on my tests) would be that running this gist will still give you ~10x speedup for structs, without hitting the CPU cache at all.

#49 by Groo on May 15th, 2017 ·

Also, regarding memory usage, my remark wasn’t that the class version used less memory, instead I wanted to emphasize that the struct version required an up to 6x larger (depending on the pointer size) contiguous memory block. Emphasis on contiguous, since individual small objects will easily find their place scattered around the heap.

For example, on a Windows 32-bit machine, max size of a single .NET process is 2GB. That’s in practice only ~1.5GB for your managed objects alone. So a .NET app running for a while and then deciding to allocate an object of (say) 600MB (that’s contiguous size, again) will be risking an OutOfMemory exception due to LOH being fragmented (regardless of GC’s efforts). For a 24B struct + 32-bit pointer case, this means you will only need 100MB contiguous space for that same array if using classes array vs 600MB contiguous space for structs, even though the class version will end up using a total of 900MB.

Perhaps rarely meaningful in practice (and this was improved in .NET 4.5.1 with a new LOH Compaction Mode), but worth mentioning for anyone thinking they can transparently swap their large class arrays for structs.

#50 by jackson on May 15th, 2017 ·

Thank you for the minimally-modified version of the code! It’s a lot easier for me to try out in the same environment to get an apples-to-apples comparison. I did so and got these results:

Notice that the time for structs is now roughly the time for classes in the article (i.e. no indexes). This indicates the structs version now has a cache miss caused by accessing the array of indices, just like there was a cache miss to access the class instance in the article. The classes version takes roughly twice as long as the structs version now that there are indices involved. This is due to the two cache misses per element: the indices array and the class instance. Since there’s hardly any actual instructions for the CPU to execute (i.e.

UpdateProjectileis cheap), the CPU time is dominated by waiting on RAM.As for memory usage, you do have a good point about contiguous memory usage. If the heap is fragmented then it’s certainly harder to find a contiguous block of memory. There are various strategies to work around this—pre-allocation, compacting GC (not an option in Unity), etc.—but like you say it’s rarely meaningful in practice. I can’t think of an example where you would want C# code to really hold an array of 10 million elements. Most data sets are likely to be only a few thousand long. That’s still plenty long to take advantage of the CPU’s caches though.

Thanks for putting together these gists and clarifying your comments! :-D

#51 by Groo on May 17th, 2017 ·

Thanks for the test, this is why to check the behavior on ARM/IL2CPP, since .NET JITter on Windows seems to produce something like:

Your test: Struct 120ms, Class 540ms (4.5x)

My test: Struct 400ms, Class 1.4s (3.5x)

But you’re right about two cache misses, I forgot that there will be a cache miss in the ProjectileClasses array too if indices are shuffled, but accessing classes through the random access array seems much slower on Windows, I am not sure why.

Anyway, thanks for the analysis!

#52 by Michael Black on May 10th, 2017 ·

I made some mods to this so it could run on a PC and got similar results…a bit over 6 times faster for the Struct solution.

Type,Time

Struct,7555

Class,45561

#53 by Theuns on May 11th, 2017 ·

Great insights!

In the early 2000’s CPUs were still struggling to keep up with RAM, so this optimisation tip would have had less of an effect back then given that RAM would have waited upon the CPU in some cases. Nowadays the picture is completely reversed and one can exploit the quick CPU cycles and their local caches.

I found this excellent article somewhat related: http://www.brendangregg.com/blog/2017-05-09/cpu-utilization-is-wrong.html

#54 by Alex on May 11th, 2017 ·

Very interesting article!

I have a program in C #. This is a program for selecting coefficients (optimization). When selecting for 2, 3, 4 arrays – the result is achieved in a few minutes for 4 arrays. And for 7 it’s already several days. Will there be a significant reduction in the selection time according to your methodology? And what needs to be changed in the program? The results are ready to be presented.

Or in this case it is better to try parallel computation?

#55 by jackson on May 11th, 2017 ·

I recommend running your program in a profiler and optimizing based on your findings. Since this is a WinForms program instead of a Unity program, you could use a tool like dotTrace or Visual Studio.

#56 by Asik on May 11th, 2017 ·

“An array of class instances therefore looks like this in RAM: 49887 32704 21426 53253 11753 71510 9790 40224 88383 ” – This is a worst-case scenario though. The GC doesn’t allocate randomly; it basically reserves a page and then increments a pointer through it, so objects that are allocated around the same point in time tend to be around the same location in memory. So your array of class instances is more likely to look like 49887 49903 49919 etc., assuming they were all allocated on array creation (probably the most typical scenario).

#57 by jackson on May 11th, 2017 ·

It might allocate sequentially, but it might not. You don’t really have any control over this. Allocation may vary by OS, IL2CPP, Mono or .NET version, VM settings, memory pressure, fragmentation, etc. Also, you might not have instantiated the classes all in a row, which is very common.

#58 by James on July 13th, 2018 ·

A lot of people here are referencing how memory will tend to be allocated sequentially in classes. This site is about Unity3D – a game engine. It’s immensely common to change the values in an array in games. In a standard piece of software, you’re looking at fairly static arrays and if something changes, a few changes in 1 second is a lot.

Games try to run at 60fps minimum, which means they only have 15ms to grind through everything that needs to be done. You don’t get 500ms, 1000ms. Things are changing extremely rapidly. Objects are being brought into existence (or modified in multiple ways if using object pooling), many times per second.

Let’s take an old game, Goldeneye 007 on N64. There’s a gun, RCP-90, which has a fire rate of 900 rounds per minute. With one person shooting one of this gun, you need to create/enable a bullet 15 times per second. Some enemies had 2 of this gun. You could have 2 of this gun. In multiplayer there could be 8 of this gun firing simultaneously. But let’s stick with 1. You pull the trigger, the gun fires. It didn’t use physical bullets, so it needed to:

cast rays, calculate collision, update the number of bullets you have in memory, write it to the UI, play a muzzle flash animation, bullet flying animation, animate the gun moving, play the sound of the gun firing and of the spent casing hitting the ground, the bullet hitting a target, be it an enemy, wall, or something else (different sound clips for each), then also the hit animation on enemies which includes blood and sparks for hitting objects (enemies included) of which there are a handful of different animations, if it hits an non-character object it will put a bullet hole overlay and play a physical damage animation as well as a smoke animation, THEN the enemies need to lose health – which varies depending on where you hit them – as do the destructable objects, which also need to change their forms if they took enough damage.

All that to shoot 1 gun 1 time. And this happens 15 times a second. The magazine capacity is 80 if you’re wondering, which means 5.33 seconds of sustained fire. And this is a simple 20 year old game. Imagine the amount of data that is going to be shuffled around to maintain all of this. Nevermind that you can hold all of the guns in a level (10-15 different sets of models that need to be available, all with different amounts of bullets, different fire rates, different animations for the gun, etc. And that you need to do it for all of the enemies as well.

Yes the GC will compact the memory to reduce fragmentation, but after a minute of combat in the game, everything is going to be wildly out of place. You can’t rely on memory to be sequential ever, even if it is when you just start the game, the level, or the program, if you’re writing standard software. Yeah it might be, but if you’re doing something that would benefit from sequential memory, then why not just do it if it’s important? Why take the chance?

The article is an attempt at helping understand that the tool exists and how to use it, and what the benefits can be. It’s a tool at your disposal. If you buy a new rubber mallet, you’re not going to go around hammering nails with it (I hope) because it’s very bad at that job. Likewise, you can use structs where it’s useful and use classes where they are better.

#59 by Rollin Shultz on August 20th, 2018 ·

Good info, but if performance is that important to a project, wouldn’t C++ be a better alternative?

#60 by jackson on August 22nd, 2018 ·

You may be able to write faster C++ code than C# code, but Unity is making that less of an issue with improvements to IL2CPP, Burst, etc. There are also other tradeoffs that a language switch entails and improved performance may not be able to make up for them. That said, if you’re interested in easily integrating C++ scripts into Unity, check out UnityNativeScripting and get access to C++, C, and even assembly.

#61 by Pieterjan Spoelders on January 4th, 2021 ·

I built a benchmark and this is pretty much spot on, still.

Without shuffle and allocating the classes in one go the struct version is usually still 2-3 times faster

Ofcourse this is because there’s relatively little going on in the background during my benchmark.

When you shuffle the records around in a large collection (1 million) it really starts to become clear,

the struct version is always about 10 times faster than the class one.

Ofcourse this might differ by machine and size and .. “luck” but you’re absolutely right here.

Enjoyed reading the article and the discussion. Just wanted to add my 2 cents in confirming this is absolutely the case.

#62 by Uğur Keskin on May 17th, 2022 ·

Thanks for article i will be using it in my project. You wrote this article in 2017, Unity Jobs System added to Unity in 2018 which is a technique that uses structs for amazing improvement in performance.

#63 by Dave on May 30th, 2022 ·

Hi there:

My team and I are having a debate. We have a class variable defined as follows:

This class level variable is set once and forgotten about – never changed during execution. However, it is evaluated easily well over 100+ times through the code in case we need certain logging info printed.

Eg, “if (DebugLogMode) Then { //print out info } ”

Would this variable be cached in the CPU by the compiler?

Or would it be cached at all?

If not, is there a way we can “force” it to be cached? Or would it be better passing it as a parameter to all the methods where it’s used?

Eg:

since local method parameters from the stack are faster than the heap?

Thank you.

#64 by jackson on May 31st, 2022 ·

Hi Dave, your class instance with

DebugLogModewill be allocated on the heap at runtime and your references to it will essentially be a pointer: the memory address of where the class instance resides in RAM. When you read a field of the class instance, includingDebugLogMode, you’re telling the CPU to read the pointer’s memory address plus some offset to the field. If this memory is in a cache, which we call a cache “hit,” then it’ll be relatively quickly read from that cache and stored in a CPU register. If it’s not in a cache, which we call a cache “miss,” then the CPU will fetch not only the field but an entire cache line. That’s typically 64 bytes, so the CPU will read the one byte ofDebugLogModeplus the next 63 bytes. That may include more fields of the class instance or something else. The requested byte will be stored in a CPU register to be accessed for “free” and the whole cache line will be stored in the CPU cache, evicting some previously-cached line. Unless you’re checkingDebugLogModevery frequently, you’ll probably have a cache miss for most of the checks.If you pass

DebugLogModeas a parameter to your functions then it’ll be allocated/pushed/written onto the stack at the time the function is called. The stack is just a particular area of RAM and this will write into the CPU cache. When the argument is read, such as inSomeMethod, it’s more likely that this read will be a cache hit since the value was just written to cache. So while you do a tiny bit more work to push the value to the stack when the function is called and pop it off the stack when the function returns, the memory access will likely be much quicker and the overall speed will be much higher since a cache miss is so very expensive.Since you say the value is never changed during execution, I’ll mention one more alternative: a compile-time setting. Consider adding a symbol such as

DEBUG_LOG_ENABLEDand checking for it with#if DEBUG_LOG_ENABLED. If the symbol isn’t defined then the code in the#ifwill be removed at compile time. If it is defined then the code will remain. In neither case will any memory need to be allocated or fetched at runtime, nor will there be a runtime check of whether the bool is true or false. The biggest downside with this approach is that you have to rebuild if you want to toggle logging on or off, but the upsides may justify this depending on your priorities.#65 by Dave on May 31st, 2022 ·

Thank you for your response and also the suggestion of adding the symbol! I’ll check that out.

FYI: we currently have our application set up with the debugLogMode passed as a parameter in most methods (the exceptions being in ‘event methods’ where we can’t. However, in those, of which two are quite long, we implemented the following:

so while assigning the local variable may involve a “cache miss”, from that point forward hopefully it’ll be stored in the CPU cache and accessed quickly.

Anyway, thank you again and appreciated your time and feedback. :-)

#66 by Chris on May 31st, 2022 ·

I’m glad I am done reading all the comments! Also… I am surprised there are two comments here above me that is latest, just May 17, and 30, 2022… this just means that future people might visit this website wooah!