Fake Functions

Today’s article is about a hack. It’s a hack dedicated to improving the performance of helper functions, nested or not. you may not like the way the code looks, but you’ll love the speed!

Arguably the cleanest way to implement a helper function for a complex function is to nest that helper function inside of the complex function. For example, consider a compare function for Vector.sort when the Vectors are grids of numbers:

public function compareGrids(grid1:Vector.<Vector.<int>>, grid2:Vector.<Vector.<int>>): int { function getGridSize(grid:Vector.<Vector.<int>>): int { var sum:int; for each (var row:Vector.<int> in grid) { for each (var val:int in row) { sum += val; } } return sum; } return getGridSize(grid1) - getGridSize(grid2); }

Rather than repeating the loop that computes the sum of all the integers in a grid, we made a helper function to do this for us and nested it within the compare function. Now, to avoid generating activation objects for this nested function and destroying our performance, we must move it out to the class level.

public function compareGrids(grid1:Vector.<Vector.<int>>, grid2:Vector.<Vector.<int>>): int { return getGridSize(grid1) - getGridSize(grid2); } private function getGridSize(grid:Vector.<Vector.<int>>): int { var sum:int; for each (var row:Vector.<int> in grid) { for each (var val:int in row) { sum += val; } } return sum; }

There are two downsides here. First, getGridSize was really just an implementation detail of our compare function and now it’s exposed to the general usage of the rest of the class. This means that it should probably be robust and do things like error handling (e.g. checking for null parameters) and we should probably document it. Ugh.

Second, we’re still doing two function calls to complete the task of comparing grids. Remember that these function calls wouldn’t be necessary if we had just been willing to write the sum-computing loop twice. Of course, that approach also has downsides. We would then need to maintain two copies of identical code, we would have sacrificed the function’s readability, and we would have bloated up our SWF with duplicated bytecode.

While I won’t be taking about readability today, the other two problems are more concrete: CPU performance to call getGridSize twice and added bytecode size of employing an extra function. So, let’s look at a third way of implementing this sorting function that uses a technique I call “fake functions”:

public function compareGrids(grid1:Vector.<Vector.<int>>, grid2:Vector.<Vector.<int>>): int { var grid1size:int; var grid2size:int; for (var i:int; i < 2; ++i) { // Setup "parameters" var grid:Vector.<Vector.<int>>; if (i == 0) grid = grid1; else grid = grid2; // Do "function" var sum:int; for each (var row:Vector.<int> in grid) { for each (var val:int in row) { sum += val; } } // Use "return value" if (i == 0) grid1size = sum; else grid2size = sum; } return grid1size - grid2size; }

Yes, this is a hack. It’s definitely not as clean as either other approach. This can be mitigated by good commenting, but it will never be quite as nice as using real functions. If cleanliness is more important than performance, you should definitely not use such a technique. However, if you’re looking for raw speed over all else to solve a bottleneck, this may be useful since it removes both function calls in favor of a simple loop that is run once per “function” call. The loop is in three parts:

- Use the loop index to set up the “paramters” to the “function”. The “parameters” are local variables.

- Do the work of the “function” and “return” values in the form of local variables.

- Use the “return values” of the “function”

These are the same steps that you go through to use an actual function, but you don’t get some of the syntactic help.

If we’re going to consider using this technique, we should make sure it actually delivers the goods and outperforms the other methods. Let’s do a performance test to see just how competitive it is. For the test, I’ve distilled down the three approaches (nested function, class-level function, “fake function”) to their most essential trait: number and type of function calls made. To do this, each function now simply computes the sum of the doubles of the first N integers. Here is the source code for your perusal:

package { import flash.display.*; import flash.utils.*; import flash.text.*; public class FakeFunctions extends Sprite { public function FakeFunctions() { var logger:TextField = new TextField(); logger.autoSize = TextFieldAutoSize.LEFT; addChild(logger); var beforeTime:int; var afterTime:int; var i:int; const REPS:int = 1000; const SIZE:int = 10000; logger.text = ",Nested,Class Level,Fake\nTime,"; beforeTime = getTimer(); for (i = 0; i < REPS; ++i) { nested(SIZE); } afterTime = getTimer(); logger.appendText((afterTime-beforeTime) + ","); beforeTime = getTimer(); for (i = 0; i < REPS; ++i) { classLevel(SIZE); } afterTime = getTimer(); logger.appendText((afterTime-beforeTime) + ","); beforeTime = getTimer(); for (i = 0; i < REPS; ++i) { fake(SIZE); } afterTime = getTimer(); logger.appendText((afterTime-beforeTime) + "\n"); } public function nested(num:int): int { function double(num:int): int { return num*2; } var ret:int; for (var i:int; i < num; ++i) { ret += double(num); } return ret; } public function classLevel(num:int): int { var ret:int; for (var i:int; i < num; ++i) { ret += double(num); } return ret; } private function double(num:int): int { return num*2; } public function fake(num:int): int { var ret:int; for (var i:int; i < num; ++i) { // Setup "parameters" var param:int = num; // Do "function" var retVal:int = param * 2; // Use "return values" ret += retVal; } return ret; } } }

I ran the test app in this environment:

- Flex SDK (MXMLC) 4.1.0.16076, compiling in release mode (no debugging or verbose stack traces)

- Release version of Flash Player 10.2.154.25

- 2.4 Ghz Intel Core i5

- Mac OS X 10.6.7

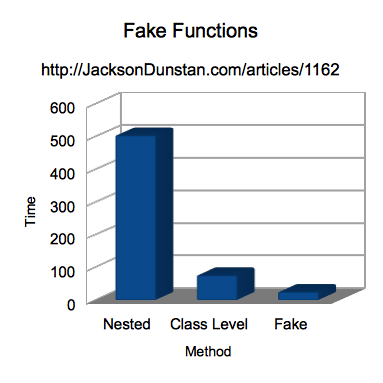

And here are the test results I got:

| Nested | Class Level | Fake | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time | 504 | 76 | 25 |

Here are those same results in chart form:

Clearly, the nested function is by far the slowest approach. Depending on your perspective, it may also be the cleanest approach because it keeps the implementation details of the function out of view of any other code. Switching to a class-level helper function makes a world of difference in performance, but a “fake function” goes one step further and results in a 3x performance gain.

If your performance bottleneck lies in a helper function, consider a “fake function” instead.

#1 by aaulia on April 11th, 2011 ·

The problem you describe in the article actually can be done by the compiler, if the compiler support inlining. This also apply to recursive function, a lot of recursive functions can be rewritten with loop (while, do, for). Unfortunately inlining is pretty hard to do for recursive function (you have to do it manually most of the time).

#2 by jackson on April 11th, 2011 ·

If only the compiler supported inlining, we wouldn’t need to resort to such hacks. :(

Still, even if it did support inlining, that would effectively duplicate the function’s body over and over resulting in a bloated SWF. So this method would still have some limited usage. What’s really needed are fast function calls. If they weren’t so painful as to cause a 3x slowdown (see article results), and only imposed a modest penalty of, say, 10%, there would be no need for this sort of technique.

#3 by makc on April 18th, 2011 ·

do you think there’s any difference in changing

if (i == 0) grid = grid1; else grid = grid2;

into

grid = grid2; if (i == 0) grid = grid1;

?

because that’s what I do :)

#4 by jackson on April 18th, 2011 ·

I’m not sure if that would help. It would seem to break down like this:

Article way, i==0: 1 if, 1 assign

Article way, i==1: 1 if, 1 assign

Your way, i==0: 1 if, 2 assigns

Your way, i==1: 1 if, 1 assign

If I were to switch to something else, I might use a ternary:

This would probably be less typing and less bytecode for larger numbers of iterations. Here’s 5 iterations:

For more on the differences between if-else and ternary, see Conditionals Performance.

#5 by makc on April 19th, 2011 ·

right, but 2 assigns case is single i == 0. for all the other i-s “if” supposed to terminate immediately, and in your form it would pass control to “else” clause. I don’t know if that’s faster or slower, hence the question.

#6 by jackson on April 19th, 2011 ·

I made two functions to encapsulate our respective ways of setting up the parameters:

Then I checked out the bytecode. They begin the same way, by setting up the local variables:

0 getlocal0 1 pushscope 2 pushnull 3 coerce __AS3__.vec::Vector.<__AS3__.vec::Vector.<int>> 5 setlocal2 6 pushnull 7 coerce __AS3__.vec::Vector.<__AS3__.vec::Vector.<int>> 9 setlocal3 10 pushnull 11 coerce __AS3__.vec::Vector.<__AS3__.vec::Vector.<int>> 13 setlocal 4Then they look like this (annotated by me):

function original(int):void /* disp_id 0*/ { // local_count=5 max_scope=1 max_stack=2 code_len=36 // ... snip common part above ... 15 getlocal1 // get i 16 pushbyte 0 // push 0 18 ifne L1 // if (i != 0) goto L1 22 getlocal3 // get grid1 23 coerce __AS3__.vec::Vector.<__AS3__.vec::Vector.<int>> 25 setlocal2 // grid = grid1 26 jump L2 // goto L2 L1: 30 getlocal 4 // get grid2 32 coerce __AS3__.vec::Vector.<__AS3__.vec::Vector.<int>> 34 setlocal2 // grid = grid2 L2: 35 returnvoid // return; } function makc(int):void /* disp_id 0*/ { // local_count=5 max_scope=1 max_stack=2 code_len=31 // ... snip common part above ... 16 coerce __AS3__.vec::Vector.<__AS3__.vec::Vector.<int>> 18 setlocal2 // grid = grid2 19 getlocal1 // get i 20 pushbyte 0 // push 0 22 ifne L1 // if (i != 0) goto L1 26 getlocal3 // get grid1 27 coerce __AS3__.vec::Vector.<__AS3__.vec::Vector.<int>> 29 setlocal2 // grid = grid1 L1: 30 returnvoid // return; }Now here’s a quick performance test:

I’ve run it a bunch of times and they’re each faster about half the time. Usually, the difference looks like this: (I chose one where your method is quicker)

original: 4897

makc: 4862

Which means that, on average, one loop might outperform the other by 0.0000000175 ms per iteration. Essentially, the two perform identically. I suspect that the same machine code is being generated by nJIT. At this level though, it’s next to impossible to discern a difference.

#7 by makc on April 19th, 2011 ·

Thanks for trying out. Not that I was expecting a groundbreaking difference (I would try it myself then :) but still nice to know for sure.